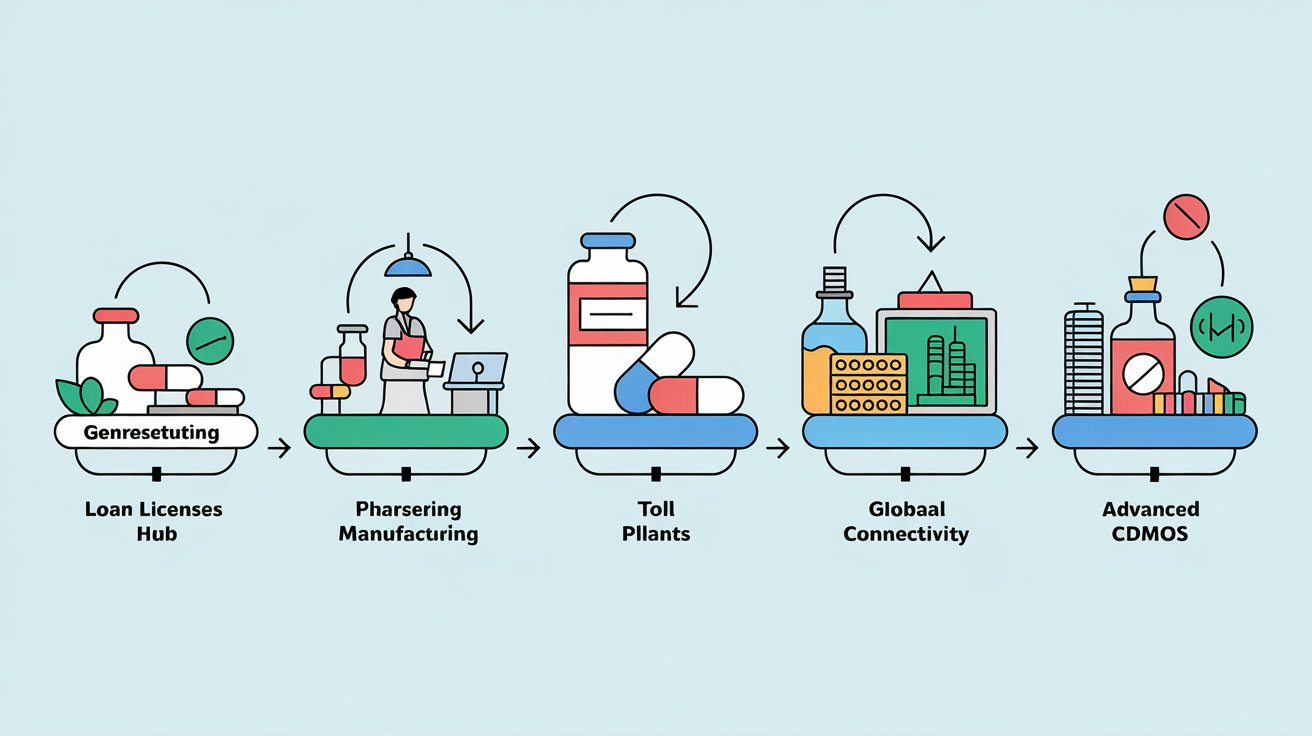

From Loan License to Toll Manufacturing and via CRAMS to now, CDMO

The pharmaceutical industry has always been a complex web of innovation, regulation, and production. Over the decades, the way drugs are developed and manufactured has transformed dramatically, especially with the rise of outsourcing models. What began as simple loan licenses and toll manufacturing in the 1990s has evolved into a sophisticated ecosystem of Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs) today. India, often called the “Pharmacy of the World,” has played a starring role in this journey. Let’s dive into how this evolution unfolded, how regulations and exports shaped the landscape, and why India is now poised to go beyond being just a pharmacy hub.

The Early Days: Loan Licenses, Toll Manufacturing, and Contract Manufacturing (1990s)

Back in the 1990s, the pharmaceutical outsourcing world was simpler but less structured. Companies relied on models like loan licensing and toll manufacturing. In a loan license setup, a company with a manufacturing license would allow another firm to use its facility to produce drugs, often under the licensee’s brand. It was a low-risk way for smaller players to enter the market without building their own plants. Toll manufacturing, on the other hand, was about outsourcing specific production steps—think of it as hiring someone to do the heavy lifting while you kept control of the recipe and branding.

Then there was contract manufacturing, a step up in sophistication. Here, a company handed over the entire production process to a third party but still owned the product design and intellectual property (IP). These models were prevalent because they were practical—pharma companies could scale production without massive capital investments. In India, this era saw small and medium-sized firms churning out generics for the domestic market, often with basic infrastructure and limited regulatory oversight from global standards.

The focus was on volume, not complexity. Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and finished formulations were produced at low cost, primarily for local consumption or less-regulated markets. India’s edge? A growing pool of chemists, cheap labour, and a knack for reverse-engineering drugs after patents expired.

The Shift: Principal-to-Principal Manufacturing (Late 1990s–Early 2000s)

As the 1990s rolled into the 2000s, a new term emerged: principal-to-principal manufacturing. This was a game-changer. Unlike earlier models where the outsourcing partner was just a hired hand, this approach treated manufacturers as equals. The contractor would produce the drug and sell it to the hiring company as a finished product, often with more autonomy in how it was made. It blurred the lines between supplier and partner, giving manufacturers more responsibility—and more opportunity.

For India, this shift coincided with the liberalization of its economy. The Patent Act of 1970, which didn’t recognize product patents, had already made India a generics powerhouse. But now, companies started eyeing bigger markets—like the US and Europe—where quality standards were stricter. This was also when the World Trade Organization’s TRIPS agreement (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) kicked in, pushing India to align with global patent norms by 2005. The pressure was on to upgrade facilities, meet Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), and compete on a world stage.

The Rise of CRAMS (2000–2010)

Enter the 2000s, and the industry took another leap with Contract Research and Manufacturing Services (CRAMS). This wasn’t just about making drugs anymore—it was about innovating them too. CRAMS combined research and development (R&D) with manufacturing, offering end-to-end solutions. Big pharma companies, facing patent cliffs and rising R&D costs, turned to outsourcing partners to develop new molecules, run clinical trials, and produce them at scale.

In India, CRAMS marked a turning point. Companies like Divi’s Laboratories and Piramal Pharma started offering API synthesis and formulation development alongside production. The model suited India perfectly—its scientific talent pool was growing, and costs were a fraction of those in the West.

Regulatory changes fueled this growth. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) began inspecting Indian plants more rigorously. By 2010, over 100 Indian facilities were FDA-approved, a testament to the country’s push for quality.

The CDMO Era (2010s–Present)

By the 2010s, CRAMS evolved into something broader: Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs). The difference? CDMOs weren’t just service providers—they became strategic partners. They offered everything from drug discovery to process optimization to large-scale production, often with specialized capabilities like biologics or high-potency APIs.

For India, the CDMO boom was perfectly timed. The global supply chain was shifting—companies wanted alternatives to China, especially after quality scandals and geopolitical tensions. India stepped up with a mix of cost, quality, and capacity. Today, the Indian CDMO market is valued at around $20 billion, growing at a CAGR of 14-15%. Analysts predict it could hit $40 billion by 2030, fueled by demand for generics, biosimilars, and complex molecules.

Regulatory landscapes evolved too. The Biosecure Act in the US, aimed at reducing reliance on Chinese suppliers, has redirected billions in contracts to India. Meanwhile, India’s own policies—like the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme)—have poured $1.3 billion into boosting domestic manufacturing.

India: The Pharmacy of the World and Beyond

India’s nickname, “Pharmacy of the World,” isn’t just hype. It supplies 20% of the world’s generics by volume and 40% of the US’s generic drugs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, India shipped hydroxychloroquine and vaccines to over 100 nations, cementing its reputation.

But the CDMO story is pushing India beyond generics into innovation and niche markets. Biosimilars, high-potency APIs, and cell & gene therapies are opening new frontiers.

Major Players and New Entrants

The Indian CDMO space is a mix of established giants and new challengers:

– Divi’s Laboratories: A $10 billion behemoth specializing in APIs.

– Laurus Labs: Expanding into biologics and high-potency APIs.

– Piramal Pharma: Focused on sterile injectables and complex formulations.

– Syngene International: Leading in R&D and biologics.

– Niche Players: Gland Pharma (injectables), Neuland Labs (peptide APIs).

– New Kids on the Block: Emerging CDMOs like APDM are bringing fresh perspectives, combining cost efficiency with cutting-edge formulations. As a new entrant, APDM aims to blend technical expertise with a customer-first approach, positioning itself as a reliable partner for global clients.

India’s Edge: Why It’s the CDMO Capital

1. Cost Advantage: 30-40% lower than in the US or Europe.

2. Skilled Workforce: 1.5 million graduates annually.

3. Regulatory Compliance: 500+ FDA-approved plants.

4. Supply Chain Resilience: Stability post-COVID.

5. Innovation Push: AI, IoT, and green chemistry adoption.

Beyond Pharmacy: The Future of Indian CDMOs

By 2030, India could capture 25-30% of the global CDMO market, up from 10% today. The shift from loan licenses to CDMOs isn’t just a business evolution—it’s a testament to India’s ability to adapt, innovate, and lead.

The Pharmacy of the World is now aiming for a bigger title: The Innovation Hub of Global Healthcare.